The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which individuals with low ability, knowledge, or competence in a specific area tend to overestimate their own skills, while those with higher ability often underestimate their competence. The theory suggests that people with limited understanding lack the self-awareness needed to accurately assess their own performance.

An ironic point about the Dunning-Kruger effect is that the very people who love to invoke it often end up being the most guilty of the behavior they criticize: overestimating their own knowledge.

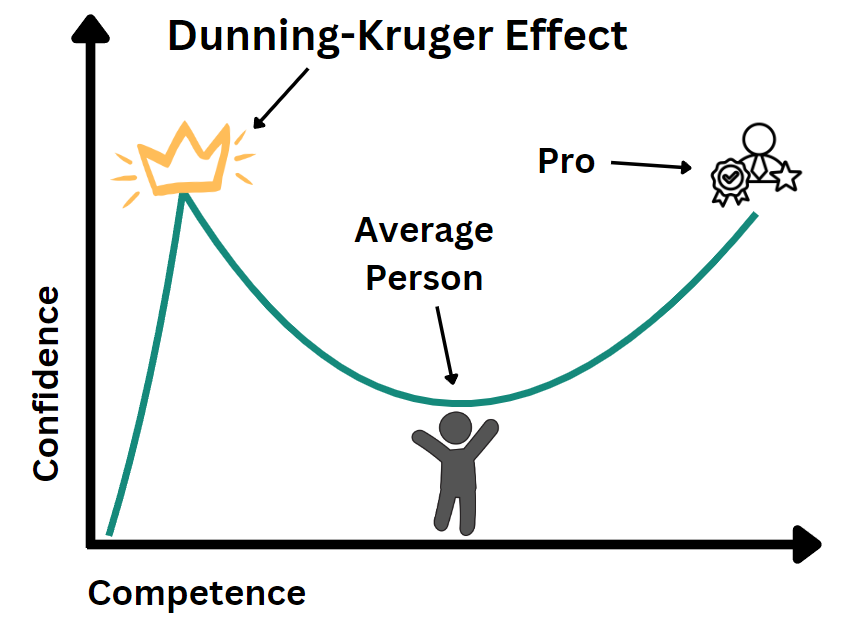

As it’s commonly understood, the Dunning-Kruger effect is a misconception. The popular graph featuring the infamous “peak of Mount Stupid” is entirely fabricated.

This fake graph suggests that the least informed are especially prone to arrogance and dramatically overestimate their abilities, while those with a bit more knowledge supposedly underestimate themselves due to newfound humility. It’s easy to see why this idea would appeal to those who enjoy self-deprecating concepts like “impostor syndrome.” However, this narrative is not based on real data.

In reality, the actual findings from Dunning and Kruger don’t show any kind of sharp peaks and valleys. Rather, their research reveals that most people, not just the least skilled, tend to overestimate their abilities. Crucially, though, the perceived ability of individuals still generally correlates with their actual ability. Those with less skill recognize that they are less skilled compared to experts, but they tend to underestimate just how wide the gap is. In other words, almost everyone overestimates themselves to some degree, but they are at least directionally correct in understanding their relative skill level.

Furthermore, subsequent studies have questioned whether the specific effect — that the least skilled overestimate their abilities more than others — even exists as a psychological phenomenon. It may simply be a statistical artifact due to regression to the mean. For instance, studies by Nuhfer et al. (2017) and Patrick McKnight at George Mason replicated the effect using random computer-generated values instead of test scores and self-assessments, casting doubt on its validity.

Nuhfer’s real-world scientific literacy tests also revealed that only 16% of people in the lowest quintile significantly overestimated their abilities, with some even underestimating themselves. He concluded that self-assessments generally reflect a person’s true competence, which contradicts the popular understanding of the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Ackerman et al. (2002) tested the Dunning-Kruger hypothesis using a correlational approach and found that individuals generally have accurate perceptions of their standing relative to others.

In 2020, Gignac and Zajenkowski tested the effect using advanced statistical techniques to control for regression to the mean, and they found no significant evidence supporting the Dunning-Kruger hypothesis. Their findings suggest that the relationship between actual intelligence and self-assessed intelligence is linear, not exaggerated as the popular version of the Dunning-Kruger effect claims.

In conclusion, the Dunning-Kruger effect, even in its correct form, is likely not real, and if it does exist, its magnitude is vastly overstated by pop psychology and media outlets.

REFERENCES

- Nuhfer, E. et al. (2017). “How Random Noise Affects the Precision of Self-Assessments of Competence.” Numeracy, 9(1).

- Nuhfer, E. et al. (2018). “The Validity of Self-Assessments in Competence.” Numeracy, 10(1).

- Ackerman, P. L., Beier, M. E., & Bowen, K. R. (2002). “What we really know about our abilities and our knowledge.” Personality and Individual Differences, 32(4), 587-605.

- Gignac, G. E., & Zajenkowski, M. (2020). “The Dunning-Kruger effect is (mostly) a statistical artifact: No relation between self-assessment and academic intelligence.” Intelligence, 83, 101449.